Plants of the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration

(west bank of the Olentangy River between Woody Hayes Drive and John Herrick Drive)

Now that I had a few weeks of my Ohio Plants class under my belt, it was time for me to explore some plants on my own and do a fun botanical survey. I now know so much more about plants than I could ever imagine– all the way from itty-bitty mosses to gigantic trees. So naturally, I MUST FIND ALL THE PLANTS! Okay not all the plants (that would be crazy…right?) Instead, I challenged myself to find a couple of new tree species, woody shrubs and vines, and some flowering plants. One extra challenge: poison ivy! Wait, what?! No, I will not be getting poison ivy, but identifying it so that I don’t get it. Get it?

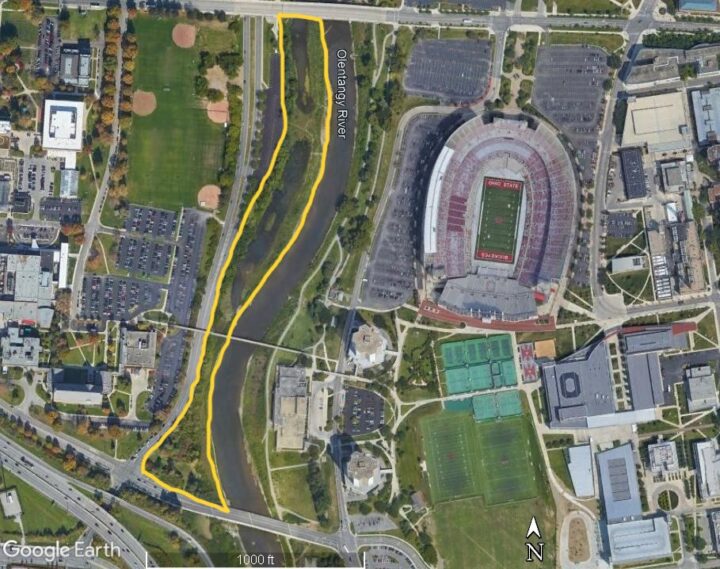

The site I chose for my botanical survey was a section of the Olentangy Riverbank. Specifically, it took place on the west bank of the lower Olentangy River between Woody Hayes Drive and John Herrick Drive. This portion of the river is part of an ongoing project to improve the wetland ecosystem of the Olentangy River after removal of the 5th Avenue Dam (FLOW). As shown in the image below, my survey took place in the vegetated areas from the river bank up to the paved areas (the road and parking lot). This ranged from grass and sedge patches to woody thickets. Being so close to the river, many of the plants I found there are ones often found along stream banks and riparian zones.

Special shout-out to George Petrides’s Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs for my identification of the trees and shrubs, and Lawrence Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide for identification of the vines and herbaceous flowering plants I saw on my walk.

Outlined in yellow is the area in which I conducted my botanical survey. The north boundary is Woody Hayes Drive and the south boundary is John Herrick Drive.

Now that you have an idea of my survey site, let’s look at what I found!

River Birch

(Betula nigra)

As I was traipsing down towards the riverbank, this tree caught my eye because it looked like it was peeling apart! However, this peeling wasn’t smooth in big blotches like the sycamores I’ve seen. This looked much more shaggy. This tree has simple, alternate leaves that are double-serrated. It is often found along stream banks. The leafstalks, buds, and undersides of the leaves feel velvety or slightly hairy. The bark peels away to reveal a reddish brown color.

Here we see the peeling bark of the river birch, revealing a reddish tint.

An early bloomer in spring, the river birch was seen as a symbol of fertility and renewal in Celtic folklore. They often used the tree as maypoles in mayday celebrations for this reason. It also served other practical uses in Native American culture as a material for canoes and water proof paper (Reiman Gardens-Iowa State University)

The simple, double-serrated leaves alternately arranged on the river birch

Black Locust

(Robinia pseudo-acacia)

Last time I went on a tree walk, I came across a honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos). While similar in name, and the characteristic of alternate, compound leaves, there are many traits of this cool species that sets it apart from its “sweet” counterpart. The leaves of the black locust are only once-compound with anywhere from 6-20 leaflets shaped like an egg. The thorns on these bad boys are paired and only 1/2 to 1 inch long. Unfortunately, I did not happen upon the pods of this tree, but they are a brown legume containing a single row of kidney-shaped seeds!

Image of the pinnately compound leaves

The kidney-shaped seeds are sometimes a food source for cottontail rabbits, pheasants, or morning doves. However, livestock may want to avoid these trees because their bark and shoots can be poisonous to them–YIKES (Petrides 77). It may be tempting, but do NOT eat the fruit of this tree because the seeds are toxic to humans (Austin 2005-Bellarmine University). On the other hand, this tree is a great nectar source for honey bees…sorry, I had to mention bees somewhere in this plant survey.

Ouch! Though they may be small, the paired thorns of the black locust are tough as nails

Now that I found some new trees, it’s time to explore the shrub and vine world of my survey site!

Buttonbush

(Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Now this shrub just makes me giggle when I say its name. Found on wet shores and in shallow ponds, buttonbush has simple, opposite leaves that are complete. Sometimes the leaves are whorled in 3’s or 4’s! What was particularly interesting about this tree was its small tubular flowers cluster together and form a tight ball. They’re as cute as a button! The leaf stalks also appeared to be a bright red color. How neat?!

After blooming for the season, the remnants of the buttonbush fruits remain hanging on the tree. Note the red leaf stalks.

Buttonbush is often listed as a poisonous plant since it contains cephalanthin, a glycosides that causes paralysis in vertebrates. However, it has also served as a medicinal plant for many Native American groups in aiding digestion, eye problems, and urinary blockages (Texas Beyond History).

Buttonbush shrub along the shore of the Olentangy River

Riverbank Grape

(Vitis riparia)

This next plant was everywhere in the wooded areas along the riverbank, just as its name suggests. This alternately arranged vine has simple toothed leaves that are heart shape. The leaves are shiny and mostly hairless with red petioles. The vines hangs off of trees and shrubs, using tendrils to climb. The bark often appears shredded and a reddish-brown color (North Carolina Extension). The fruits of riverbank grape are a blue-black and taste bitter.

The leaves of the river bank grape trailing on the ground.

Many mammals and birds eat the berries of this plant, and even humans can enjoy this slightly bitter fruit dried, fresh, or turned into jelly. North Carolina State Extension recommends accurately identifying fruits like these before consuming because some very similar looking ones are toxic!

An up close look at a tendril wrapped around another plant

Here are some of the other plants I found flowering!

New England Aster

(Aster novae-angliae)

This bright purple beauty caught my eye in the midst of tall beige and browns plants. It is a member of the Asteraceae family, so it has both ray flowers and disk flowers! While there were many asters represented at my site, I determined this to be the New England aster using a few characteristics mentioned in my Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide. This particular aster has 40-50 ray florets with a large amount of disk florets. The leaves are not toothed and lance shaped.

A look at the New England aster next to goldenrod

This aster has many pollinator friends around shores and wetlands. They include bumble bees (my personal favorite) and are a great source of nectar for monarch butterflies getting ready for migration (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center)!

Up close look at the purple ray flowers and yellow disk flowers

Obedient Plant (False Dragonhead)

(Physostegia virginiana)

I almost missed this plant walking by because many of its companions had lost their flowers already. But this plant was obedient and let me take a picture of its cool flowers. Growing in a spike inflorescence, these irregular flowers had a rosy hue to them. Their lance-like leaves were sharply toothed and arranged oppositely. The insides of the petals have dark purple-pink spots running down them.

Here we see the spike inflorescence of the obedient plant

The obedient plant gets its name because it tends to stay in the position it is planted for some time (Newcomb 94). And guess who is it’s most important pollinator…BUMBLE BEES (Illinois Wildflowers). Can’t you just imagine a chunky little bee butt poking out of that tube?

An up close look at the flowers of obedient plant. Notice the bilateral symmetry and perfect entryway for a bumble bee!

Poison ivy

(Toxicodendron radicans)

Never in my life did I think I would be so very sad to not find poison ivy. I looked everywhere for this nasty little sucker and was just having the worst luck (ironic, right?) Eventually, I found some climbing up a tree…and then I found more and more all around! Poison ivy can grow in many forms: shrubs, climbing vines, or trailing vines. The leaves are in groups of three and vary in the amount of lobes. If climbing as a vine, they have many aerial rootlets that make the vine appear hairy on the surface it attempts to conquer. The stalk of the middle or end leaflet is often longer that the two on the side. Poison ivy produces fruits that look like clusters of small white balls.

Trifoliate leaves of poison ivy. Leaf size can range from 4 to 14 inches!

Fortunately, I have never had the chance to see if I am allergic to the oils this plant produces. Many people who are often get blisters and itchy, irritated skin. Despite these qualities, the fruits are still enjoyed by many game bird species that aid in dispersing its seeds (Petrides 81).

Notice the hair-like roots climbing up the tree

The white fruit of poison ivy

Now equiped with all this knowledge, I plan to keep on exploring my site and identifying everything that I can along the way!

Plants of the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration: the Sequel

I’m back, and with more plants from my field site than before! This time, I am looking at the the Coefficients of Conservatism and Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) for my site, similar to what I did for Cedar Bog. As a refresher, the Ohio Floristic Quality Assessment Index (OFQA) assigns a coefficient of conservation (CC) to each plant species, created by Andrea et al. (2002).

The Coefficient of Conservatism (CC) is a value ranging from 0-1o that indicates how conservative the species is in regard to the community in which it is found (with lower values being plants that can survive in a multitude of disturbances and habitats and higher values indicating high-quality habitat). The Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) uses a mathematical formula to average the CCs from a list of plants at a site to determine an estimate for the site’s quality.

After some exploring of my site, I’ve generated a list of trees, shrubs, vines, and some herbaceous plants that I found to calculate the FQAI for the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration area. This is by no means every species I saw. It only includes native species, and just a fraction of the total I saw.

Native Plant List for FQAI

Common Name (Scientific Name) – CC

- Ohio buckeye (Aesculus glabra) – 6

- River birch (Betula nigra) – 9

- Slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) – 3

- Box elder (Acer negundo) – 3

- Black willow (Salix nigra)– 2

- Sandbar willow (Salix exigua) – 1

- Red oak (Quercus rubra) – 6

- American elm (Ulmus americana) – 2

- Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) – 0

- Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos) – 4

- Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) – 7

- Wild crabapple (Pyrus coronaria) – 3

- Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) – 4

- Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) – 6

- Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) – 5

- Silky dogwood (Cornus amomum) – 2

- Riverbank grape (Vitis riparia) – 3

- Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) – 1

- Fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica) – 3

- Common greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) – 4

- Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolium) – 2

- Button bush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) – 6

- Swamp rose (Rosa palustris) – 5

- Tall boneset (Eupatorium altissimum) – 0

- Wingstem (Verbsina alternifolia) – 5

- Obedient Plant (Physostegia virginiana) – 5

- New England Aster (Aster novae-angliae) – 2

- New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis) – 3

- Dotted smartweed (Persicaria punctata) – 6

- Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) – 1

- Tall Ironweed (Vernonia gigantea) – 2

- Common Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) – 1

- Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) – 1

- Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum) – 1

- False nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica) – 4

- Mistflower (Eupatorium coelestinum) – 3

- White vervain (Verbena urticifolia) – 3

- Leucospora (Leucospora multifida) – 5

- Common Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia)- 0

- Long-leaved tooth-cup (Ammania coccinea)- 7

- Water-purslane (Ludwigia palustris) – 3

- Climbing false buckwheat (Polygonum scandens) – 2

To calculate the FQAI for my site, I added up all of the CC values and then divided by the square root of the number of species in my sample. The FQAI I calculated for the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration site is 21.76. According to Andreas et al. (2002) and their categorization of this value, this site is right on the cusp of having “high vegetative quality.” However, this list does not include non-native species, of which I found a lot. I’d be curious to see how those influence the habitat quality assessment.

Below I will explore in depth some of these plants. Any identifying features or facts for trees, shrubs, or woody vines comes from Petrides FIeld Guide to Trees and Shrubs and herbaceous plants from Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide, unless otherwise noted.

Four High CC Valued Plants

River birch (Betula nigra) – 9

As described above, the river birch has alternate, simple, double-serrated leaves and shaggy reddish-brown bark. The leaves are often velvety on the underside, with a white appearance. The buds and leaf stalks also feel hairy. This tree is a great specimen for controlling erosion along stream banks (Arbor Day Foundation)

This tree grow best in bottomlands and next to bodies of water (ODNR). This tree has an extremely high CC value, meaning it has high preference and tolerance to certain habitat requirements. Since I found this tree in the bottomlands near the Olentangy River, that must mean that area fulfills this habitat requirements!

Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) – 7

An alternate, simple-leaved plant, this tree is easily recognized by its mottled bark. The bark peals away in large flakes to reveal a yellow-white underbark. The bases of the leafstalks cover the buds, and stipule scars encircle the entire twig. The fruit of the tree is a ball-shaped multiple of achenes. Cavities in sycamores provide nesting areas for wood ducks, opossums, and raccoons.

Another tree found near bodies of water naturally, it the higher CC value indicates that its tolerance for habitats other than moist lowlands is relatively low. Once again, the riverbank of the Olentangy must do a good job suiting those needs.

Long-leaved tooth-cup (Ammania coccinea) – 7

This herbaceous wetland plant has simple, opposite leaves that are arranged perpendicular to the pairs of leaves above and below it. The flowers form clusters that are sessile to the stalk. The leaves may appear heart-shaped at the base or even clasp the stalk. long-leaved tooth-cup, also known as the scarlet toothcup, belongs to the loosestrife family–just like the highly invasive purple loosestrife (Minnesota Wildflowers). Many ducks feed on the seed capsules in the fall and winter as they dabble and forage in the mudflats (Illinois Wildflowers).

The high CC value is assigned to this plant because of its restriction to mudflats and muddy banks. Since I found this plant in the mudflats of the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration, the mudflats there allow the long-leaved tooth-cup to grow within it!

Dotted smartweed (Persicaria punctata) – 6

The racemes of this plant are lined with little green or white flowers. They have alternate leaves that are narrow and lance shaped. The surface of the leaves are covered in pitted dots–one might even say they are dotted. It’s often found in wet meadows, marshes, or fens (Minnesota Wildflowers). The shorter depth to their nectar reserves makes dotted smartweed and attractive plant to short-tongued Halictid bees, which are often referred to as sweat bees (Illinois Wildflowers).

As I mentioned before, the dotted smartweed is found in wetter habitats, like flooded meadows, fens, marshes, and ponds. It persists best in these habitats, which is why its CC value is higher than some others.

Four Low CC Valued Plants

Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) – 0

This tree has alternating leaves that are pinnately compound with egg-shaped leaflets. But I am sure you already know that from reading the description above from my first site visit. The leaf scars of the twigs are almost circular, and younger twigs have paired thorns surrounding those scars. As a part of the legume family, this tree is great at fixing atmospheric nitrogen for the soil. The legumes of this locust are much smaller than the honey locust pods.

This tree has a very low CC value at zero! While it is native to Ohio, the black locust can easily crowd out other native vegetation. It can grow in a variety of habitats, such as woodlots, disturbed sites, or fence rows. It’s not very picky–earning it a whopping CC of 0.

Tall Boneset (Eupatorium altissimum) – 0

A member of the Asteraceae family, this white flowering plant has opposite, toothed leaves that have 3 prominent veins down them. THe plant consists of many rayless, white heads, often having a flat-top appearance to them. They are usually found in prairies and open woods. Boneset gets its name from its use in soothing bone aches that accompanied bad fevers (University of Arkansas).

This plant received its 0 CC because it is commonly found in a variety of habitats, not too picky. I found tall boneset close to the river, up by the road, and everywhere in between.

Common Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) – 0

Like the last plant, common ragweed is a member of Asteraceae with opposite (sometimes alternate), toothed leaves. The flower heads are in racemes and are staminate (no pistils!). The flowers are a green color, but very small. This species sometimes provide valuable food resources to birds in the winter since their racemes will stick above the snow (Illinois Wildflowers). Also, you can blame this plant for those wonderful late-summer allergies.

As the name suggests, this plant is common. It’s CC value of 0 is warranted because it can practically grow anywhere. It’s often found along roadsides and cultivated areas, like pictured here.

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) – 1

Pokeweed can get over 3 feet tall, with pink-white flowers in a raceme. At this time of year (fall), the fruit of the pokeweed plant are dark purple berries that stand out in the green of the woods. The leaves are entire and opposite. Don’t be fooled by the beautiful berries. The birds may love them, but the berries and root are poisonous (potentially lethal). Before the young shoots turn pink, they are edible as greens, and the early colonists used the berries as dye (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center).

Pokeweed is often considered a weed because of its ability to persist in disturbed habitats, open woods, thickets, and roadsides. Because of this ability to persist in many habitats, pokeweed gets a low CC value of 1.

OH NO! Invaders!

There were some awesome native plants all around the survey site, but unfortunately there were LOTS of invasive plants. Here are some I found around the area.

Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

Like some of the native walnut trees, the tree-of-heaven had alternate compound leaves that are pinnate. But despite its name, this tree is anything but heaven. Highly invasive due to rapid growth, I found this tree all throughout my survey site. It has very large leaf scars, and a scratch-and-sniff test does not yield a pleasant smell. It was first brought over as an ornamental plant, but soon became a nuisance with its ability to grow almost 8 feet a year, quickly dominating other native plants.

Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana)

Callery pear has alternate, simple leaves. The tear-drop leaves are very finely toothed, thick, and waxy. The branches form upright, acute angles. It was planted as an ornamental and sometimes called “Bradford Pear.” Originally introduced to the US in the 1900s, the Callery pear was brought as a way to graft domestic pears, but it escaped cultivation. It is highly invasive because roots and seeds persist if not dealt with properly. (Penn State Extension)

Porcelain Berry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata)

In the same family as native grapes and the variation in their leaf shape, porcelain berry is sometimes hard to identify. The leaves are alternate and deeply lobed with 3-5 lobes (UMN). The flowers are arranged in an upright, umbrella shape that remains upright with the berries even if other parts of the plant droop (VNPS). Many mammals and birds will eat and spread the berries, but it can also reproduce asexually from its roots (Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden).

Cut-leaf Teasel (Dipsacus laciniatus)

Cut-leaf teasel has opposite leaves that form a cup around the hollow stem. The leaves are deeply lobed, unlike the common teasel, and the bracts do not extend past the flower heads. By this time of year, the cut-leaved teasel is done flowering and leaves a dead, dry stalk in its place. Above- and below-ground parts of the plant must be removed because of its ability to form deep, strong taproots. It was originally brough over to raise fiber naps of fabrics on spindles. (Minnesota Department of Agriculture)

Substrate-Associated Plants

Like we learned about substrate picky plants for the two sides of Ohio, we can find some of those plants here at the Lower Olentangy Ecosytem Restoration. At this site, we are in the western limestone-based areas of Ohio that were once glaciated. That means many of the plants we find are calciphiles. Here are some that Jane Forsyth said are likely to be found in this area based on the substrate based on her Geobotany article mentioned in other posts. (I have to say–I couldn’t find too many of Forsyth’s picky-plants, but the ones I did find made sense based on her article.)

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Hackberry trees have simple, alternately arranged leaves with rough leaves that have uneven bases. The bark of this tree often looks warty or bumpy when mature. The branches also appear to spread out flat. Forsythe describes this tree as a tree generally limited to limy substrates, and my site falls in the part of Ohio with a limestone base.

Fragrant Sumac (Rhus aromatica)

Next on Forsyth’s lime-restricted plant list was fragrant sumac. Luckily this is not poison sumac (Rhus vernix) in which all parts of the plant are a skin irritant. This thornless trifoliate shrub has alternate leaves with large teeth. They produce a fragrant odor when crushed, hence the name (also another reason I am glad this was not poison sumac because crushing those leaves would NOT be pleasant). The buds of this shrub are quite fascinating and are tightly packed into spike-like shapes (Petrides 81).

Red Oak (Quercus rubra)

Now this plant was not necessarily restricted to limestone substrates, but Forsyth does say this tree is characteristic of clay-rich, high-lime substrates. Red oaks have simple, alternate leaves that are deeply lobed with pointed tips to the lobes. The red oak is used frequently as lumber for veneer and furniture, and its acorns are an important source of food for animals like turkey, squirrels, and deer (Bates Canopy).

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

Forsyth claims that this tree also occurs frequently in the till plains of western Ohio, but not just because of substrate! It is a prairie-margin tree, found along the eastern borders of western US prairies, but also the prairies that used to occupy Ohio. It has alternate simple leaves, like the other oaks, but the lobes of this “white oak” species does not have bristle-tips. The leaves also have at least one deep pair of indentations, dividing the leaf into two sections. Since this tree is fairly fire-resistant, it is able to withstand the natural fires of prairies compared to other trees (Iowa State University).

Well, that’s it for my site and the Lower Olentangy Ecosystem Restoration site. I had a blast going through the woods, the meadow, and the mudflats around the river. I encourage you to go out and explore the plants around you. I know I have a much deeper appreciation for them after all of this. I can’t wait to continue my plant-learning journey! Thanks for going along with me!